HOW THE SOUTH WAS LOST

CAN IT BECOME BLUE AGAIN?

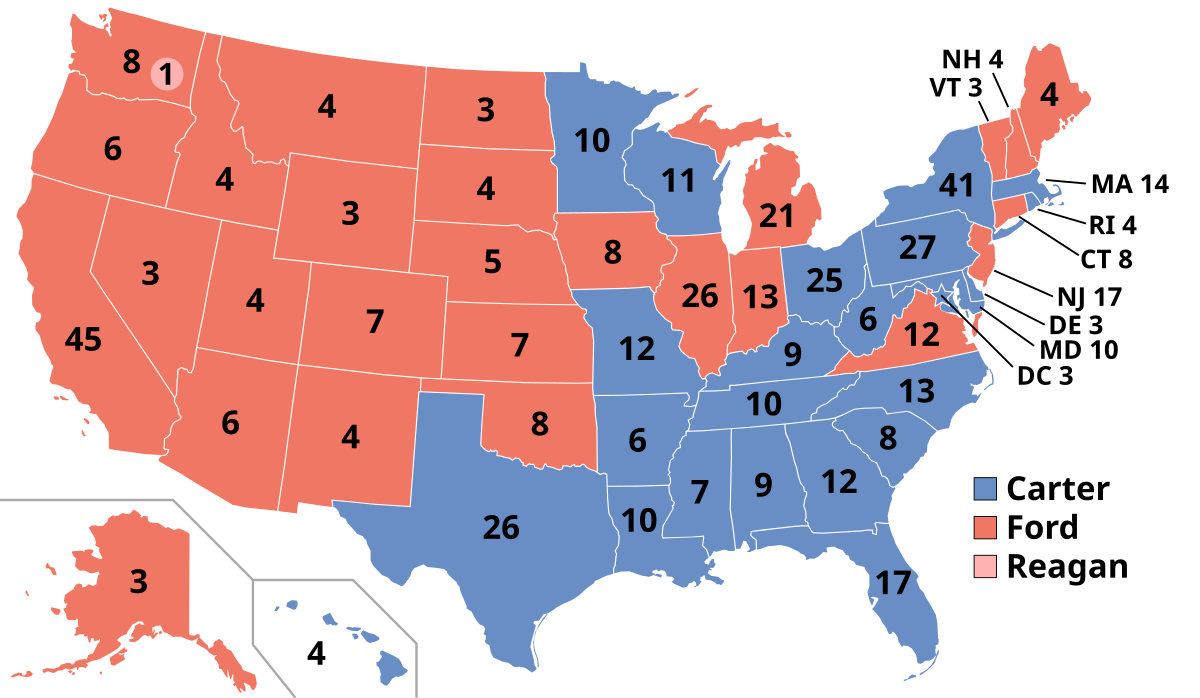

Here’s the map from the 1976 presidential election. Jimmy Carter defeated Gerald Ford 297 to 240.The orange is Republican and the blue is democrat. The south was what carried it for Carter. What has brought such a massive change today and could it ever change again?

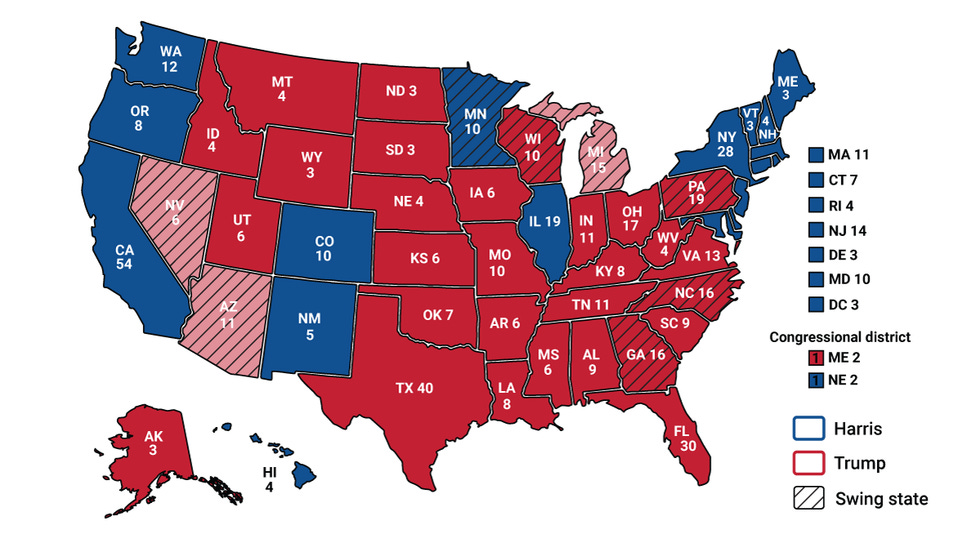

Here’s the red and blue states map from the 2024 election won by Trump. He won 312 to 226 in the electoral college.

When Jimmy Carter entered into the White House in 1977, riding on his outsider status and his roots as a Georgia governor, the United States’ electoral map was wired in a way that seems almost alien today. The Deep South, long the bastion of the Democratic Party, delivered for him. But fast-forward to the Donald J. Trump victory in 2024, and the red states dominate confidently including large stretches of the South. What happened in between? And what does it mean for a party that wants to win the South back?

In 1976, the map still held vestiges of the “Solid South” Democratic era. Carter—himself a Southerner and a Southern Baptist. Southern white voters still reliably pulled the lever for Democrats. By 2024, however, the tables had turned: deep in the heart of the red-state South, Republicans stand strong and Democrats struggle to maintain footholds.

The Democratic coalition then still included large numbers of white Southern voters, many of whom felt that the Democratic Party was theirs, rooted in regional identity, patronage politics, and an older order. Carter’s victory wasn’t an anomaly; for decades the South was the “our” territory of the Democrats, even as the rest of the country shifted.

Now fast-forward to 2024. The electoral map shows a Republican resurgence—not just in the traditional heartland, but across the South and even in places that once leaned more flexible. Trump’s sweep of the swing states, his strong showing among white working-class voters, and even gains among segments of minority communities have made the red map larger and more durable.

So how did we get from there to here? A Nation Divided from the Start

The story begins long before Carter or Trump, back with Lincoln, slavery, and the war that tore the country apart. In the 1800’s, the Republican Party was born out of opposition to the expansion of slavery. Abraham Lincoln’s election in 1860, on a platform that sought to prevent slavery’s spread, triggered Southern secession and the Civil War. The South, dominated by slavers and plantation economies, saw Lincoln’s victory as an existential threat to its way of life.

When the war ended in 1865 and slavery was abolished, the Republican Party became the party of Union, emancipation, and Reconstruction, while the Democratic Party, especially in the South, became the home of those who resisted Reconstruction and fought to restore white dominance. For nearly a century after the war, the South voted solidly Democratic, not because of liberal ideals, but because the Democrats were the party of segregation, states’ rights, and white supremacy.

This was the era of Jim Crow, from the 1870s through the 1950s, when Southern Democrats built systems of voter suppression, racial terror, and legal segregation to keep Black citizens powerless. The “Solid South” meant one-party rule. Black citizens were largely disenfranchised through literacy tests, poll taxes, and intimidation, while the Republican Party became a small, marginalized presence.

Yet the seeds of change were growing. In the early 20th century, as millions of African Americans migrated northward, they began to vote where they could. For a time, they remained loyal to the party of Lincoln. But that began to change during the Great Depression.

Franklin D. Roosevelt’s New Deal in the 1930s transformed American politics. For the first time, many working-class Americans, black and white alike, looked to the federal government for economic relief. Even though New Deal programs were often administered through segregated Southern systems, Black families benefited, and many began to see the Democratic Party as a champion of the poor and working class.

This marked the first slow realignment. Northern Democrats became more progressive, while Southern Democrats clung to segregation. Tensions grew within the party.

When President Harry Truman desegregated the military in 1948 and introduced a civil rights plank into the Democratic platform, Southern delegates walked out and formed the Dixiecrat Party, nominating Strom Thurmond for president. It was a clear warning that the South’s loyalty was conditional, and that civil rights could break it.

The 1950s and 60s brought that break. The Civil Rights Movement, led by Black Southerners and their allies, forced America to confront its original sin. Under Presidents Kennedy and Johnson, the Democratic Party began to embrace civil rights as a moral issue, not just a political one.

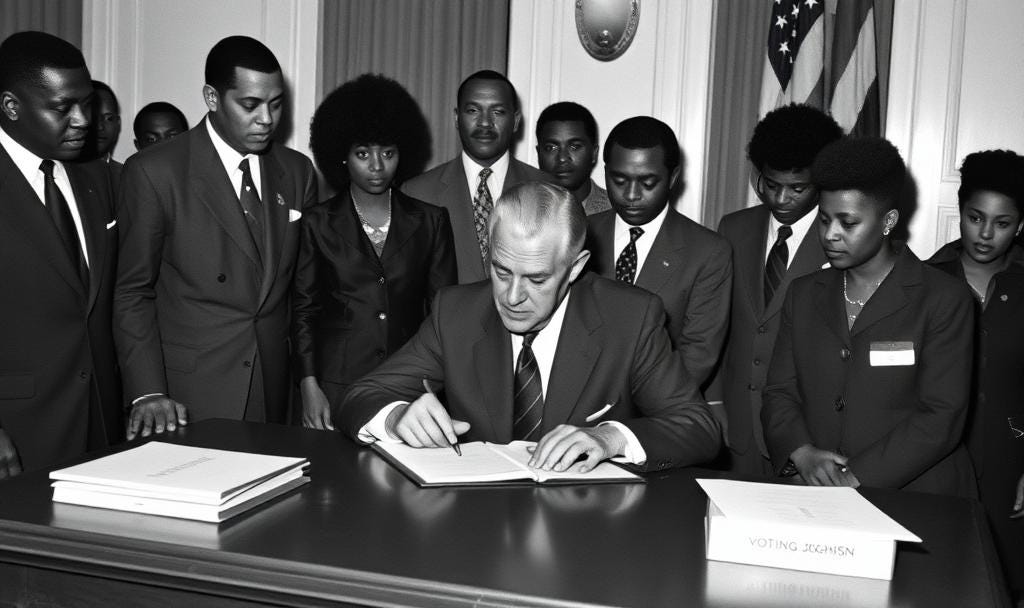

When Lyndon B. Johnson signed the Civil Rights Act of 1964 and the Voting Rights Act of 1965, he famously told an aide, “We have lost the South for a generation.” He was right.

Many white Southerners felt betrayed by what they saw as federal overreach. The Republican Party, seeing opportunity, began to speak to their resentment through coded appeals to “law and order,” “states’ rights,” and opposition to “big government.” This became known as the Southern Strategy, first under Barry Goldwater in 1964, who opposed the Civil Rights Act, and was later perfected by Richard Nixon in 1968.

The Rise of the Religious Right

In the years that followed, a new kind of political movement took root, one not built on race or economics but on religious identity and cultural anxiety. Many conservative evangelicals, who had largely stayed out of partisan politics for most of the 20th century, began to mobilize in the 1970s.

The catalyst was complex: a mix of backlash against the sexual revolution, school desegregation, the feminist movement, and the 1973 Roe v. Wade decision legalizing abortion. Leaders like Jerry Falwell, Pat Robertson, and later James Dobson framed these issues as moral battles for the soul of the nation. The “Moral Majority” and later the “Christian Coalition” helped forge a powerful voting bloc of white evangelicals united around abortion, traditional family values, and opposition to what they called the moral decline of America.

For many Southern believers, this movement offered a sense of moral clarity and belonging. The GOP, seeing their potential, embraced the language of faith, family, and patriotism as defining features of conservatism.

Democrats, meanwhile, often struggled to respond. In defending pluralism, women’s rights, and LGBTQ+ equality, they came to be perceived as hostile to religion and traditional family life. That perception, fair or not, has lingered for decades.

If Democrats ever hope to regain traction in the South, they will need to reclaim moral language without surrendering their convictions: to speak of justice and compassion not as secular ideals but as expressions of shared moral concern. The challenge is to honor faith without weaponizing it, and to show that caring for families, protecting children, and nurturing communities are American values.

By the 1980s, Ronald Reagan’s brand of optimistic conservatism, small government, lower taxes, “family values,” and a strong national defense, cemented the South’s Republican turn. White evangelicals, once politically quiet, found a home in the GOP. The Democratic Party, increasingly defined by its commitment to racial justice, women’s rights, and social liberalism, became the home of the diverse coalition it represents today.

By 2024, that long transformation was complete. The “Solid South” is still solid, but now solidly Republican. The states that once delivered the presidency to Jimmy Carter now form the backbone of Trump’s coalition.

But the picture isn’t static. Georgia flipped in 2020 and again in 2022, electing Senators Raphael Warnock and Jon Ossoff. North Carolina remains competitive. Texas’ urban centers Dallas, Houston, Austin, are changing. The South of 2024 is not the South of 1976.

If Democrats are to regain ground, they must understand what was lost relationally. For much of the 20th century, Southern Democrats spoke the cultural language of their region. They were churchgoers, farmers, and small-town neighbors. They understood that politics in the South is as much about belonging as belief.

Rebuilding trust means starting at the ground level. It means showing up in rural towns, partnering with churches, listening to working families who feel left behind. It means reframing issues like healthcare, wages, diversity and education not as abstract policies but as moral commitments to the common good.

Because history shows that the map can change. The parties have traded places before, and they may again. The South that once stood for segregation now boasts some of the most dynamic, diverse cities in the nation. The future of the Democratic Party in the South may depend on whether it can see it as fertile ground for renewal, not as an enemy that must be conquered.

The transition didn’t happen overnight. It unfolded through decades of realignment, racial, cultural, economic, and generational.

By the time of the 2024 map, the South had largely consolidated as a Republican stronghold—a landscape where Democrats rarely carry entire states and often must rely on minority turnout, multi-ethnic suburbs, or urban cores to stay competitive.

Could Democrats Win It Back?

Yes, and no. It’s possible for the Democratic Party to recapture parts of the South, but it would require a new kind of strategy, narrative, and local identity. The map doesn’t easily flip, especially when party identity in a region becomes a kind of cultural badge. Any hope of turning blue parts of the red South would likely hinge on generational change, demographic shifts (especially urban growth and minority populations), and sustained investment in local organizing, not just national messaging.

First, Democrats must embrace fielding candidates who understand regional traditions, faith communities, and the daily struggles of working-class Southerners, without being out-of-touch from rural life.

Second, the economic message matters more than ever. The South today is being left behind by globalization, automation, and shifting industries. A Democratic message grounded in opportunity, fair wages, infrastructure investment, and community revitalization could resonate, but only if tied to credible local leadership.

Third, Democrats must speak the language of values, not just policy. Beyond healthcare or tax reform, the story must be about dignity, community, family, faith (yes, faith), and the idea that “we’re in this together.” Too often Democrats are perceived as dismissive of those values; to flip parts of the South, they’ll need to show they respect them.

Fourth, any hope of undoing the red map in the South will take time, not just a campaign cycle. Republican dominance in many Southern states is rooted in decades of party-building, messaging, and institutional control. Democrats will need year-round presence, local infrastructure, and patient work to change minds and habits of participation.

What the Map Could Look Like Tomorrow

Imagine a Southern state map where Georgia doesn’t just flick blue for presidential votes, but also returns more Democratic governors, mayors, and state legislators. Where North Carolina transforms suburb-by-suburb. Where even a state like Texas becomes closer, not solid red—but one where Democrats are competitive and winning enough to change the electoral math.

That doesn’t mean the South turns into New York or California overnight. But if the Democrats can re-establish themselves in the South—not as outsiders but as partners in regional renewal, they might repaint parts of the map.

In the end, the red states of today didn’t turn ruby red by accident—they turned that way because the Republican Party found an identity that resonated with many Southerners, while the Democrats gradually drifted away. To reverse that, the Democrats must not just campaign harder, they must change how they show up.

And the first step might simply be believing the South is not lost. Because only then can the map shift again.